The new year is the time for political risk firms to release their outlooks for the year ahead. Usually, these come in the form of Top-10 lists – items that I read and enjoy, but that I don’t really like.

That’s not to say that these lists are wrong. They are written by intelligent people, who are working hard to understand and explain the evolving global environment. But reading these lists is a bit like watching cable news in IMAX. Sure, you get a lot of good information, but it’s simply not the right format.

There are three reasons why the classic Top-10 list isn’t well-suited for political risk.

First, they bundle together lots of very different types of risks. The decoupling of the United States and China (including in terms of economics and manufacturing) is very different from Artificial Intelligence. But to have a list where they’re both present and roughly equal is, if not wrong, certainly a bit odd. Are we really saying that ChatGPT and an invasion of Taiwan are similar enough to sit next to each other?

Second, and much more importantly, there is no such thing as universal political risks. Political risk is not like the temperature, where we can say that, objectively, the weather in New York today is 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

Every organization has their own set of risks that pertain to their own operating environment. A company with factories in Hungary is going to be highly exposed to any European Union sanctions on the country, and will monitor these accordingly. The same company may not care much about a trade war between China and the United States, even if that would be, by any objective definition, a far larger political risk for the planet.

Of course, companies cannot put out thousands of Top-10 or similar lists tailored to each potential reader, but it does lend a bit too much of an air of authority and definiteness to the topics that are on the list.

Third, these lists don’t tell anyone what to do about those featured/selected risks. It’s a bit like if a doctor told you about a bunch of diseases that people can get. Sure, it may be interesting to learn about cholera, but I’d rather know what illnesses I’m vulnerable to and, crucially, what I can do about it. A list of risks gives readers food for thought, but it’s easy for them to close that reading tab and then move on with their day.

A better annual risk list

With help from my former colleague Dr William Arthur, I decided to introduce the first-ever Two Lanterns Annual Guide to Political Risk. You can download the report as a PDF here

Our goal here is not to say what the top risks for the next twelve months are. Instead, this guide is imagining what we would do if we were appointed to be in charge of managing political risk for an organization and how we might structure our thinking and - crucially - our next steps over the next twelve months.

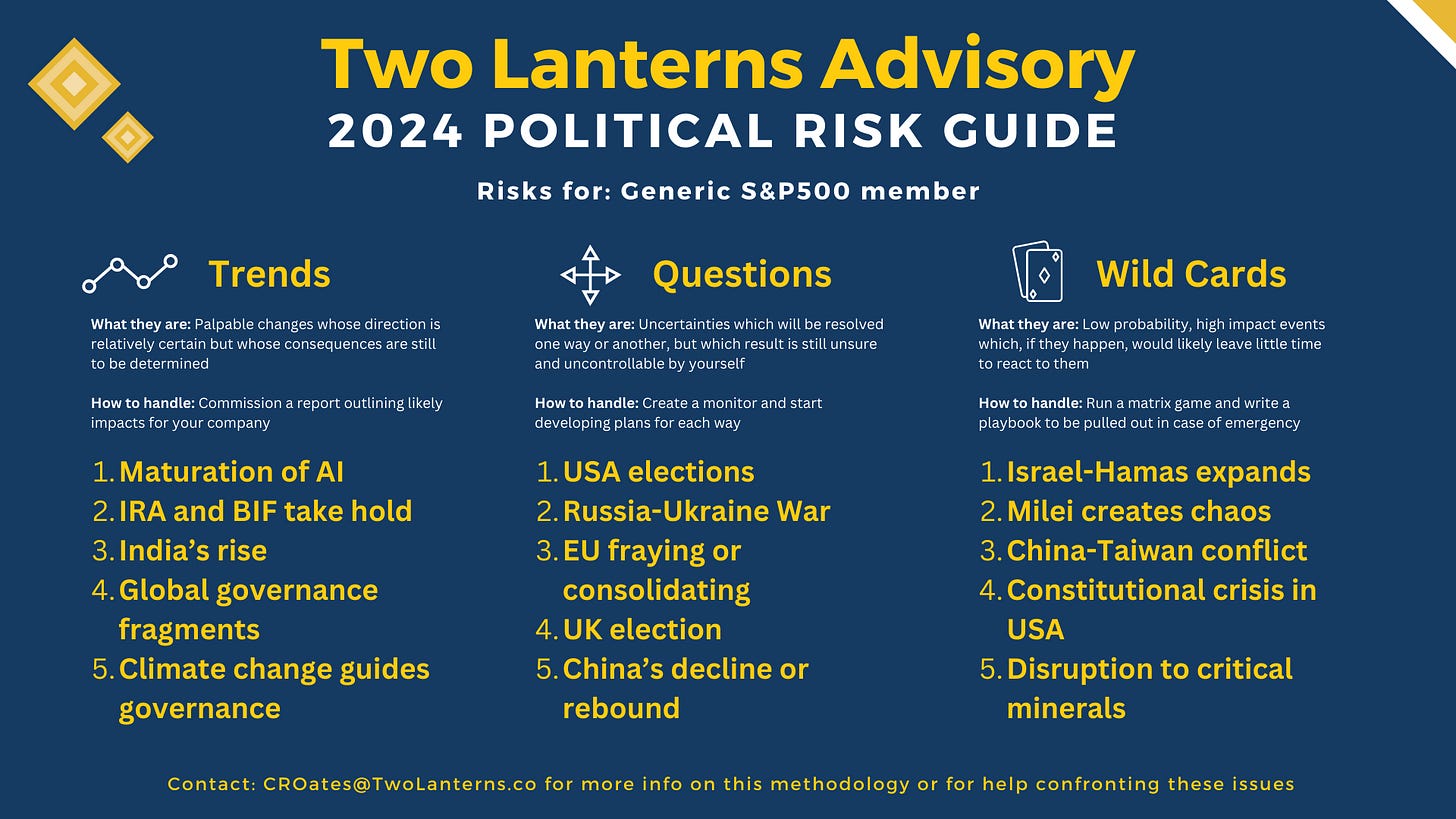

We start by breaking down risks into three categories:

Trends: Things that are somewhat predictable in their development but whose second-order consequences are unknown but highly important. Climate change is an example: we know it’s likely going to be hotter in five years than today on average, but we don’t know all the ways this trend will manifest.

Questions: Things that we know matter but which we don’t know the outcome of. An election is a good example: one candidate will win but we don’t know for sure which. However, we can look at the candidates running and their stated policy preferences, and construct an idea of what might happen in each direction. The election’s result could take us into wildly different futures, but we are by this method far better prepared than if we sat and waited for the votes to come in and then began the risk analysis.

Wild cards: Things that probably won’t happen, but if they do, would dramatically alter the landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic was a major wild card. No one predicted it specifically, but a pandemic was on the list of bad things that could happen to the world, and indeed it did come up in analysis conducted before COVID-19 – analysis undertaken to build a risk list for clients for the coming months and years. Ultimately, COVID-19 upended the entire world in many ways, from the economic to the social, to say nothing of the massive health impacts across various geographies and diseases. Those countries that had pandemic preparedness plans in place tended to do better than those that didn’t.

We obviously can’t write about every trend, question, and wild card in the world, so we’re going to focus on five in each category that would apply to a generic US-based multinational corporation. Each individual company would have a different list, as would a government agency, non-governmental organization, and so forth. But we hope that this list includes a broad enough array of items that at least some of them would apply to anyone reading this note today – and that it offers a starting ground for your own work in conceptualizing and mitigating risks. Of course, if you’d like a list tailored to your own needs, please get in touch.

We also offer some advice on how to handle each category, plus a preliminary forecast for each item. As noted, each forecast is based on a time frame of one year from now and is, of course, simply our best assessment at the time of writing.

With that, on to the inaugural Two Lanterns Annual Guide to Political Risk.

Trends

A trend is something that is already palpable and which seems likely to continue developing in the same direction.

Take for example the rise of Germany in the late 1800s: it was clear to governments in Europe that Germany was growing in economic and military strength after its unification from smaller states. By December, Germany would have more guns, ships, and factories than it had the past January. The question for policymakers therefore became one of what to do with that knowledge, thereby framing and guiding then-contemporary debates.

For a trend, the best preparation can be done by commissioning a specific report. An internal or external writer working for your organization can interview some experts on the trend or conduct some quantitative analysis, to help identify how the trend will affect your sector in particular. These reports can be tailored to different risk horizons – in our professional lives, clients have asked for reports that look ahead a matter of days or weeks, or on other occasions decades into the future. Listing a set of impacts and recommended responses provides guidance for your team’s plans for the year. This can usually be done within two months.

Trend 1: Maturation of Artificial Intelligence

Landscape: The debut of ChatGPT at the end of 2022 led to a hype cycle rarely seen in the tech sector, where being AI-enabled seemed to be enough to get venture capital funding. We’re now starting to see evidence of which parts of the AI revolution are real and which are novelties.

Impact: Businesses that have staked it all on AI could see their assumptions shattered by a single action by a regulator or competitor.

Preliminary Forecast: At least one major AI assumption will be broken. The current leading contender is a lawsuit on copyright infringement against large language model or ‘LLM’ developers requiring astronomical licensing fees that change the unit economics.

Trend 2: Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework (BIF) policies start to be felt in United States

Landscape: In 2022, President Joe Biden signed the BIF and the IRA, both of which he’s touted as the centerpiece to his ‘Bidenomics’ agenda. But since the wheels of government do not move overnight, we are now starting to see programs and investments come into shape.

Impact: Both laws will have a significant economic impact incentivizing clean energy production and spurring new infrastructure projects. But the political impact for Biden’s chances in November 2024 to be re-elected remain to be seen.

Preliminary Forecast: As the United States spins up new industrial production, other countries will look at similar packages of their own and the European Union will reconsider whether it needs more spending on its Green Industrial Deal.

Trend 3: India’s rise

Landscape: As of 2023, India became the most populous country in the world. Its economy is growing and its geostrategic heft is seen as an opportunity for the United States to counter China.

Impact: The United States has long seen India as a counterweight to China in the Asia-Pacific – even expanding that region to the Indo-Pacific in 2018. Navigating that relationship will throw new challenges to Washington that it may not be prepared for.

Preliminary Forecast: US-India relations will become more complicated this year, as structural geostrategic forces come up against questions of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s policies – particularly within the US Democratic Party. However, economic ties will likely be unaffected.

Trend 4: Global governance architecture fragmenting

Landscape: Current global governance architecture dates from at least 1945, but the world has come a long way since then, and new powers are challenging the status quo.

Impact: Any sustained and significant change in global trade, security, and diplomatic architecture will open the door to policies that would have been unthinkable a decade ago, creating new uncertainties and opportunities.

Preliminary Forecast: From the US-China trade war to the war in Nagorno-Karabakh, we’ve started to see actions that had been prevented by prior international rules and norms. This year will likely see more, though the exact manifestation is yet to develop specifically.

Trend 5: Climate change as a guiding principle of government

Landscape: Carbon-neutrality is becoming a justification for government action in a number of areas, either due to the importance of fighting climate change or to not allow other countries to win the race to a green economy and technologies.

Impact: Climate-friendly policies that did not politically pencil due to opposition will be more likely to pass as their arguments in favor become more potent – much like how many policies in the United States post-1945 passed because they had a tangential relationship to the Cold War.

Preliminary Forecast: Advocates for and against policies will tout the climate impacts as primary arguments, especially if green subsidies and investment from governments are at stake, and regulatory efforts to prevent greenwashing will become more prevalent.

Questions

There are many things in political risk that we know matter but don’t know the outcome of. Elections, wars, legislation – these are all what pundits and professional analysts obsess about being able to predict correctly. All are important for the typical risk analyst at a company.

However, analysts often don’t have the luxury of being able to make a single prediction and only plan for that outcome, because in the case of questions, more than one outcome is possible. If analysts are wrong about their prediction, then their firm – or their firm’s clients – will be left in the difficult position of being unprepared for what has ultimately happened, if only a single forecast was made and it turned out to be partly or wholly incorrect.

One of the best ways to mitigate this danger is to conduct a scenario-based analysis. The first step is to identify your company’s goals/threats/opportunities and where, when and how these might be achieved. The next step is to factor in all of the elements that could affect these and monitor them. This allows you to stay on top of the risk – even adding new scenarios and/or removing old ones – as new developments and evidence arise. In a sense, you are constructing a forward-looking model that can function as a roadmap and risk guide within your organization.

One of the best ways of setting up a scenario-based analysis – especially within a company or for clients – is to put together a workshop designed to develop the goals you hold, the ways you might achieve them, and the risks facing you. Collaborative analysis increases team buy-in to the exercise and company’s operations but also, crucially, offers an opportunity to iron out survivor and confirmation biases, while identifying as many relevant scenarios as possible for your company.

With your team, brainstorm how each possible scenario outcome would affect your company and what you might do about it, both before the fact and afterwards. For example, it is possible to draw up a policy roadmap for if the Democratic or Republican presidential candidate in the United States wins the next election – or the unlikely possibility of a third-party candidate winning – and then to put plans in place accordingly, for example, how you should model your clean energy investments in each scenario. Once the winning candidate is known, you have already had months to get ready for it.

Question 1: US elections

Landscape: The presidential election will dominate news coverage, but policy in 2025 will be shaped as well by this year’s elections for Congress and at the state level.

Impact: It is hard to overstate how dramatically different US policy could be in 2025 depending on the outcome of these elections. Organizations should have plans for all combinations of Democratic and Republican control of Washington and the states in which they operate.

Preliminary Forecast: Biden will win the White House and Democrats will retake the House of Representatives in Washington DC, while losing the Senate. We stress that this is a preliminary forecast.

Question 2: Russia-Ukraine War

Landscape: The war since February 2022 continues. Ukraine is still reliant on foreign military and economic aid (something that now appears to be faltering in commitment) while both militaries struggle to achieve offensive breakthroughs.

Impact: The war will be a major determinant of the state of Russia-Ukraine, Russia-West and West-China relations in coming years.

Preliminary Forecast: International will to support Ukraine will remain but pressure on Kyiv and Moscow will grow for a negotiated settlement while neither side is able to overcome the defensive power of minefields, drones, and trenches.

Question 3: European Union fraying or consolidating

Landscape: EU solidarity increased when Russia invaded Ukraine but dissent from Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orban, and possibly others, threatens the cohesion of the Union.

Impact: Regulations, economic policy, and security arrangements are all shaped by the overall political direction of the bloc, which will be shaped by national and European Parliament elections this year.

Preliminary Forecast: The far right will likely make gains in the European Parliament. This will halt, and maybe reverse, some of the bloc’s economic policies and will very likely lead to more anti-immigrant policies being considered.

Question 4: United Kingdom election

Landscape: The next UK general election must be by 28th January 2025, although the current prime minister has said the poll will come later in 2024.

Impact: The election could end Conservative Party rule. They’ve led the United Kingdom since 2010 under five different prime ministers to date. Labour could take over, with a decade’s worth of pent-up policy proposals, with the debates in 2025 surrounding which ones to prioritize.

Preliminary Forecast: The Labour Party will win an outright majority and Sir Keir Starmer will be the new prime minister. Whether he delivers on his promises is a question for next year’s Two Lanterns Annual Guide to Political Risk.

Question 5: China’s decline?

Landscape: In the last two years, China’s economy has started to falter, with meltdowns in the important real estate sector, and dramatic policy changes hitting sectors hard, like a ban of private tutoring decimating that sector.

Impact: China’s rise categorically challenges the current economic and military superpower: the United States. Any shift here will be seismic, especially if it looks like we have witnessed ‘peak China’, with demographic trends pointing to a steady downturn in its power.

Preliminary Forecast: We have not hit peak China. The country’s economic growth may be slowing, but it is still growing, and Beijing is still translating its wealth into military and diplomatic power. However, President Xi Jinping’s domestic standing will be of greater concern and the policy environment could become more volatile.

Wild Cards

Harold Macmillian was prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963, having previously held a host of ministerial positions in the years before that. He is reported to have been asked what the greatest difficulty was for governing, and to have replied “Events, [my] dear boy, events” to his questioner (the reported quotation varies slightly in form).

Despite all the best planning and forecasting, Macmillan had seen UK government cabinets roiled by what the world threw at them. Inside the world of political risk, analysts will say a similar thing, referring to ‘black swan’ events, which are entirely unexpected, or to ‘gray swan’ events, which are partly anticipated.

These wild card events are those that are not obvious in advance of them happening. Wild card events are not like elections – where the outcome and timeline can be fully or largely predicted in many cases – but are instead out of the blue events that are low probability and yet high impact. For risk professionals and operational managers, such events are difficult to plan for, since they could come at almost any time and in many different flavors.

The key is to brainstorm with your team all of the low probability, high impact events that you can imagine happening and which would have an impact on your business – the only way to reduce how ‘wild’ a wild card can be. The outcome could be to the downside, where your operations and plans could suffer, or to the upside, where there are opportunities to be harnessed – given effective foresight and risk planning. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic was a wild card event (even though pandemics per se are easily conceivable) and yet when it became clear that widespread societal lockdowns were on the way, it became possible to envisage the jarring economic and social effects of these – and then to make long and short investments in the stock market in response, for instance.

For wild card events, we recommend running a matrix game, which allows the assumptions and interconnections in these situations to be put under the microscope. For example, when Trump and Biden were facing each other in the 2020 US presidential election, both candidates’ ages were highlighted among media commentators, including from the standpoint of what would happen to the electoral process should one or both candidates be incapacitated during this period. This would have been a seismic development, but it was possible to game out what could happen in this scenario and to identify which party might be hurt/helped more by it, thereby increasing their odds of winning the White House.

A playbook can then be developed to help guide an immediate response by your company should the given wild card come about. If such wild card events start looking more likely, they can then be bumped into the Questions risk category highlighted above, and tracked more precisely with a dedicated risk monitor, perhaps with additional scenarios added.

Wild Card 1: Israel-Hamas war expands into other countries and threatens Red Sea

Landscape: The current Israel-Hamas war has been largely confined to Gaza, although Hezbollah in Lebanon and Houthis in Yemen have made some moves towards involvement.

Impact: The war in Gaza has had tremendous political effects and – of course – even greater humanitarian consequences, but has largely not hit markets. That could end if the war expands to a wider Israel-Iran war and commercial shipping becomes a target.

Preliminary Forecast: As with all of these wildcards, this is a low-probability event. But one sign of a coming expansion would be if Israel appears to be planning to invade southern Lebanon, which would spark a pre-emptive attack from Iran-backed proxies.

Wild Card 2: President Javier Milei throws Argentina into chaos

Landscape: Argentina’s new president has vowed to get rid of bureaucracy and dollarize the economy, but the courts have already started blocking some of his reforms – throwing open the question of which of his promises will become policy.

Impact: Argentina is a G-20 economy, though a struggling one. Ill-considered economic policies could send it into a recession and drag down growth elsewhere in Latin America.

Preliminary Forecast: We expect much of Milei’s radical manifesto policies to be watered down or blocked, and for political drama to take time to reach the regulatory and business environment.

Wild Card 3: China-Taiwan conflict

Landscape: China’s government wants to ‘reunify’ Taiwan with the mainland. Chinese cyber, economic, and military capacity is growing, and a Taiwanese election this year could trigger a move from Beijing.

Impact: Any Chinese move on Taiwan will test allies’ resolve to defend the island and a war would disrupt the global economy far more than Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Preliminary Forecast: January 2029 will likely see US presidential handover due to term limits. Beijing could invade Taiwan during the handover, which makes a 2024 attack much less likely.

Wild Card 4: Constitutional crisis in the United States

Landscape: There are a number of glaring gaps in the US constitutional order that would allow the will of the people to be disrupted by events. If Biden and current Vice President Kamala Harris were to both die and be replaced by the Republican speaker of the House; if multiple Supreme Court justices were to be incapacitated without replacement; or if states began ignoring federal laws, there are not clear indications about what might happen.

Impact: Political chaos does not often translate into outright market instability, but it would likely mean that few new regulations or laws would be passed, and those that are would be uncertain to ever be enforced.

Preliminary Forecast: There are a number of flavors of potential crisis, but they would most likely all involve a protracted budget standoff that leads to an extended government shutdown, since that is where political dysfunction meets real deadlines.

Wild card 5: Disruption to critical minerals

Landscape: Many of the most important products used in our economy rely on a small number of commodities. The US federal government has a national strategy for securing the supply of 35 of these, but the Government Accountability Office has said that this strategy does not fully address how agencies should implement it, what it would cost, and what it aims to achieve.

Impact: A disruption in supplies to these minerals, whether from conflict in production areas to stockpiling from processing countries, would throw key industries into disarray, much like how the auto sector was disrupted by a semiconductor chip shortage during the pandemic.

Preliminary Forecast: The exact source and target of a disruption cannot be precisely forecasted, but it seems unlikely that the United States will have a robust resiliency plan in place by the end of the year – thereby leaving companies still vulnerable to a crisis.

What to do with all of this

Even at 4,000 words, we’ve had to leave out most of what could be said about all of these risks, nor could we dive into the relevance of each to every organization with someone who might be reading it.

If you’re working at a place that may be exposed to political risk in 2024 – whether one of the above risks or something else – the key is to do something about it. Use this guide as a starting point and begin discussing with others whether any of these risks pose a particular threat to your work, or if there are others that would be more important.

Commission a report, build a monitor, or create a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency playbook – whatever is suited to the risk at hand that you face. You can contact us for work on any such projects or advice on how to take care of it in-house.

What’s important is that you are actively thinking about what could happen before it does. That’s what makes political risk different from the news – it shapes your work and you can work to better address it.

About Two Lanterns Advisory

Two Lanterns was created to address a gap in the political risk market - the analysis that people are left to do on their own. We have three main ways to help you:

The Political Risk Academy, an online course with live sessions to teach you a comprehensive methodology for practical political analysis.

Consulting projects, for when your needs are greater than what your own team can handle in a timely fashion or when you want coaching on building a team or addressing a particular situation.

Our newsletter, Inside Political Risk, serves as a resource for political analysts, with best practices, industry updates, and guest posts from others in the field.

Contributors to this report

Dr. Chris Oates, Founder, Two Lanterns

Chris founded Two Lanterns Advisory, a political risk consultancy, where clients include the Department of Defense, financial institutions, and multinational corporations, and Legislata, an informational platform for the policy world. He has also served as a Senior Advisor to Voter Choice 2020 and has worked at Oxford Analytica. Chris has a PhD in International Relations from the University of Oxford and a BA from Brown University. He is a Lecturer at the Pardee School of Global Studies at Boston University.

Dr. William Arthur, independent consultant, ex-Oxford Analytica

William completed his doctorate at Oxford University in 2014 and worked for geopolitical consultancy Oxford Analytica from late 2011 to late 2023. William ran the firm’s Southeast Asia and then North America & Asia-Pacific desks in his time, before moving to the consulting department, ending as a manager. He is currently an independent consultant.