Why are Elon Musk and a venture capitalist talking so much about Ukraine?

Why being overly successful can be an obstacle to analysis

(This was published in the grIP Venture Studio brief. If you have any startup needs, get in touch with them.)

The Dunning Kruger Effect is, to state it bluntly, that some people are so incompetent they can’t recognize how incompetent they are.

Think of Michael Scott from The Office. His character is socially inappropriate, tone deaf, and cringe-inducing. Because he’s so oblivious, he fails to pick up on all the signs that he’s oblivious. Most sitcoms have at least one character that fits this bill and, unfortunately, so do many workplaces, and you may know someone like this.

Recently, we’ve seen the opposite phenomenon on display from the richest person on the planet and a tech entrepreneur with nine figures of wealth. People who are so successful and, presumably, so competent, that they make basic errors when wading away from their areas of expertise. And their actions show why every corporation should have a dedicated political risk advisor who isn’t the CEO.

Musk and Sacks

I’m speaking about Elon Musk, CEO of Tesla, SpaceX, and now Twitter, and David Sacks, formerly COO of PayPal and a major investor in Silicon Valley.

Both men have gone online recently to promote what has been described as a pro-Russian view of the war in Ukraine. Musk tweeted out a proposed settlement to end the war that Ian Brimmer says came directly from Vladimir Putin and that Fiona Hill says shows that Musk is being played.

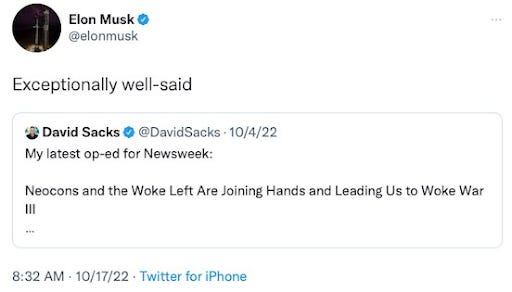

Sacks has taken to calling the war in Ukraine “Woke War III.” He also has been taking the line that the war needs to end, basically on Putin’s terms. Musk has approved of this.

This could be a simple example of people having different opinions of the Ukraine War than the consensus in DC. But these are not two random Twitter users saying this. One is the richest man on the planet. The other is highly influential in the venture and startup communities. Both have platforms for their views far greater than the average person that makes their statements of consequence to their own careers.

Their past professional success shows that, whatever else, they cannot be deemed wholly incompetent or naïve. They have both achieved professional successes far beyond many of those disagreeing with their views on Putin.

That, however, appears to be the reason they are going so far out on a limb here.

Geopolitical hubris

Precisely because Musk and Sacks have been successful, they have the self-confidence to go against conventional wisdom.

All startup founders and entrepreneurs faced skepticism that their plans would work out, or that what they claimed to be seeing in the dynamics of the market or technology were real. Taking something from an idea to a billion-dollar exit takes an almost superhuman ability to ignore naysayers. But it doesn’t take much to drift from “contrarian” to “ignoring all evidence to the contrary.”

The result is that Musk has been called a “useful idiot” for Putin by journalist Julia Ioffe. Sacks published this column that is littered with basic errors. Among other howlers, he argues that “the Left has now joined with neocons to oppose Obama’s restrained foreign policy in Ukraine.” This ignores that Obama is in favor of the current support to Ukraine or that the situation on the ground has changed slightly from when he was in office.

Political risk lessons

What does this mean for companies considering how they can manage political risk? And what does it mean for the analysts trying to talk to their bosses about how to handle it?

It means that their smartest executives may be the worst positioned to make an assessment. Their success and skills in their business roles may be unquestioned. But that success could blind them from the gaps in their knowledge about other areas, like international politics.

So how should a company deal with political risk? There’s no single right way to manage it, but here are three key steps you should drill into your executive team’s minds.

First, have humility.

You may be the most brilliant person you know. You workday may be a rapid succession of triumphs. But be aware that your customers are not autocratic leaders, your products are not diplomatic standoffs, and so your experience might not be applicable to geopolitical situations. If you are taking on political risk solely by yourself, be aware that you’re likely to make a mistake.

Second, formalize your approach.

There’s no way to avoid dealing with the wider global environment, so accept that you’ll have to think about where politics is going. Treat it in the same way that you would any other challenge in your business. Some options are:

Set up an internal committee to consider the major risks you face and set deadlines to ensure the committee does not bog down in speculation and chatter.

Identify analysts who seem promising in this area and train them to better understand the topic.

Commission reports on the biggest risks you face from outside political risk advisors or specialty firms and accept that they likely know more about those situations than you do.

Third, revisit it regularly.

Political risk may ebb and flow, but it never goes away. New risks and opportunities emerge. Old concerns fade. New techniques for analyzing events are introduced. If your solution is a committee, have it meet every quarter. If it’s training, have your analysts regularly attend workshops. If it’s outside consultants, keep them on retainer or book new projects in advance.

Through a serious approach to this issue and recognizing that success in business does not necessarily translate to success in political analysis, your executive team can navigate choppy international waters without risking your reputation by an ill-considered op-ed.