Boris Johnson became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland yesterday.

As the betting markets showed, he had been the presumptive favorite since the leadership race was announced. He quickly took a lead and, except for a drop that coincided with Michael Gove’s bounce, maintained his lead through a Jeremy Hunt bubble, a Rory Stewart boomlet, and Jeremy Hunt again.

Three years after the referendum on Britain’s EU membership, it has a PM who campaigned for the winning side. As Johnson put it in his acceptance speech, “we are going to get Brexit done.”

This raises the question: How?

Politics is arithmetic

I’m regularly annoyed the journalistic tendency to portray politics as a series of dramatic narratives and heated policy debates when, most of the time, it’s about simply counting votes.

Brexit is no different. There are only three outcomes for what could happen.

Britain leaves the European Union without a deal on October 31.

Britain leaves the European Union with an agreement.

Britain does not leave the European Union.

The problem with the Boris coverage is that choosing one of these options almost certainly requires a majority in Parliament.

The House of Commons has voted against a No Deal before and has taken steps to ensure that Johnson cannot follow that path against its wishes.

Parliament has also voted against the Withdrawal Agreement as negotiated by now-almost-former PM Theresa May.

Parliament has also voted against holding a second referendum or repealing Article 50.

The question for Boris Johnson is not, therefore, what he will do. It’s what he can get Parliament to agree to when it currently does not agree on any approach.

Complexity within a simple question

Okay, so we’ve gotten Brexit from the wooly coverage of the PM campaign down to the central question of what would change the parliamentary math. Now we run into the problem of predicting the actions of 650 individual politicians, many of whom are not following party leadership, limiting our ability to forecast their actions. They are now led by a politician whose former boss said he “would not take Boris’s word about whether it is Monday or Tuesday,” so we can’t rely on his statements.

However, political risk analysts can’t simply throw our hands up and be done with it. Our job is to provide clarity about what is more or less likely, and what we would be likely to see en route to that direction.

We have to be able to start to unravel the threads, or at least clarity what are the worst tangles.

Forecasting Parliament

One of the most detailed approaches I’ve seen comes from the writer and analyst Jon Worth, who has created a series of flowcharts, with probabilities at each decision point, to generate overall probabilities of the different outcomes.

The latest full chart can be found here and I’ve included a snippet below of what would happen after a vote of no confidence in Parliament. The highlighted numbers are the probabilities that each path would be taken from the previous scenario.

Worth argues that the highest probability is a snap General Election before the fall. If the Conservatives take a majority, they could push through the Withdrawal Agreement with enough votes to spare, especially if the party campaigned on it and new members felt an obligation to do so.

Other analysts are starting to talk about that possibility and bookies are now offering shorter odds on an election in 2019 than in 2022 when they’re next scheduled.

Five-party politics

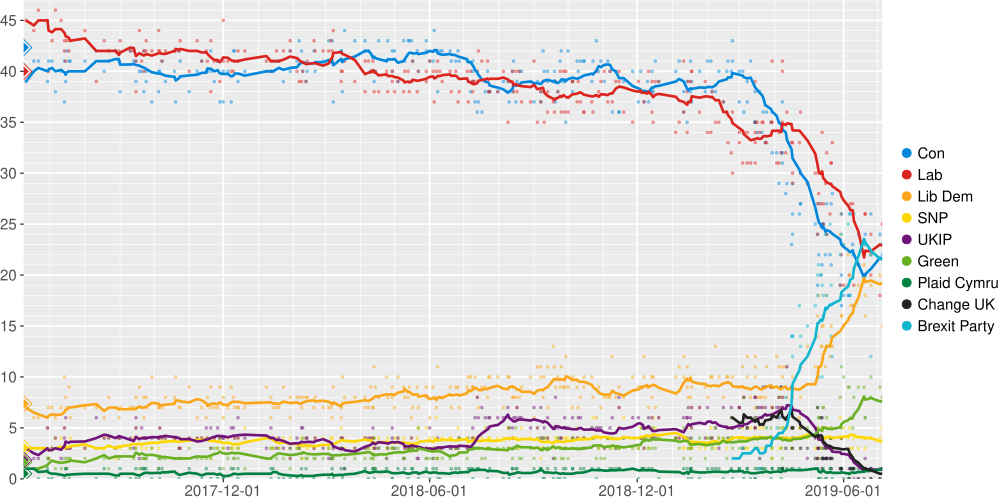

Unfortunately for analysts, even being correct that there will be a General Election doesn’t do much to tell us what will happen. UK politics is extraordinarily scrambled right now. Polls show that four parties are roughly equal in polling intentions, with the Greens in a historically strong position.

However, the UK votes in a first-past-the-post system that means we cannot simply extrapolate national polling to seat totals. In 2015, the UK Independence Party received 12% of the vote for 0.2% of seats, while the Tories turned 37% of the vote into 51% of seats.

Electoral Calculus, a great polling analysis and forecasting site, finds that even small changes in vote totals could have huge swings in how many seats are won. A 1 percentage point difference in vote share is estimated to change the Conservatives seat total by 4% of seats.

This is especially important given the volatility in the electorate. In the 2017 election, Labour shot up the opinion polls during the campaign as previously disenchanted supporters rallied behind the chance to win seats and take control of the government.

Labour and the Conservatives now face the reverse situation. The European Parliament elections in May saw seats proportionally allocated, so the parties could easily fracture. The Brexit Party halved the Conservatives’ strength and the Liberal Democrats and Greens did roughly the same for Labour.

Forecasting a General Election is therefore almost impossible. If Boris Johnson is able to bring most Brexit Party voters to the Conservatives, bringing their national polling position close to 40%, while Labour and Lib Dems stay at 20-25%, the Conservatives could receive a huge majority government, according to Electoral Calculus’ prediction model.

If the reverse happens - or Labour, Lib Dems, and Greens form some kind of alliance and coordinate to prevent vote splitting - then Labour could receive an outright majority, or at least enough to form an anti-Brexit coalition with the Lib Dems and SNP.

This doesn’t give us the answer, but it helps to identify the central question: which side of the political spectrum comes together more rapidly if a General Election is called.

If we see that Labour is repeating its 2017 performance, that’s a sign that Johnson’s decision has backfired and a second Brexit referendum is likely. If the Brexit Party stumbles, outpaced by the deeper and wider electoral infrastructure of the Conservative Party, expect a big victory for the Tories and the Withdrawal Agreement passing.

These are two widely divergent scenarios, but both show the way to what matters most in the months before October 31.

This situation will be monitored throughout the summer and fall, and future issues will assess whether this analysis was correct or, like so many predictions about Brexit so far, wildly off-base.

Chris

About Two Lanterns

Two Lanterns Advisory is a political risk consultancy based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. For information on training courses in political risk, hiring a consultant, or commissioning reports, check us out at http://www.twolanterns.co.