On Monday I launched the Two Lanterns Platform, the first software-as-a-service for political and country risk.

Since the pandemic started, I’ve thought a lot about the nature of political risk.

Part of this was that I needed to shift my business viable towards a remote age. Part of it was that without commuting, rec soccer, dinners with friends, or bars to watch sports, I had time on my hands to think about the structure of this industry.

Political risk has fascinated me ever since my first day on the job. The content is inherently interesting - we get to analyze everything important in the geopolitical world and tell people what we think will happen.

But it’s also interesting from a business perspective. Political risk feels like an industry that is simultaneously mature and in its infancy. The leaders have been in business for decades but the proliferation of new techniques means that a solution that disrupts everything is always possible.

The Two Lanterns Platform is my attempt at that solution, (although it aims to be less disruptive and more constructive to the existing industry). For a detailed breakdown of the platform, you can go here.

But I thought that, since this is a newsletter for people interested in the world of political risk, you might want to know how I see the problems of the industry, where it’s missed out, and why this platform can improve it.

The analysis of the business model of political risk is a little long, so I’m going to divide it into three parts. Stick around for the next two.

The Long Tail

There are two major obstacles to adequately satisfying a political risk question, both from the perspective of an organization needing political risk advice (the client) and the one providing it (the consultant).

The first is that most questions are hyperspecific. We are sometimes asked a question that everyone wants to know, like “who will win the US presidential election?” But often we’re asked something like “what is the risk of expropriation for my gold mine in Armenia over the next ten years?”

This phenomenon was captured by Chris Anderson when he was arguing why e-commerce would be a huge hit.

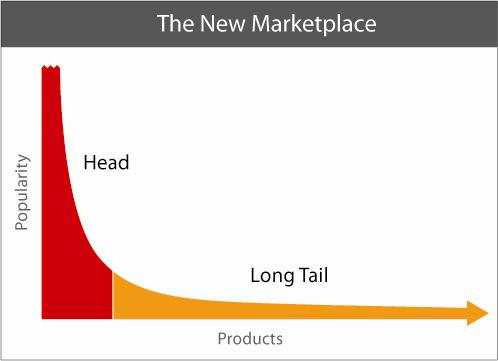

The long tail exists in a market in which there are a few products with really high popularity - let’s say a PlayStation 5 - but also lots of products with low popularity - for example, a vintage tabletop NFL game from the 1970s.

In the past, the costs of distribution and limited store space meant that businesses could only stock and sell high popularity products. Think about your typical bookstore. It has bestsellers, maybe some other books, but you won’t be able to find that out-of-print niche title from 1948.

Now, Amazon can store nearly everything in its warehouses across the country and sell them on a single retail site. eBay can connect interested buyers and sellers across the world. The profitability limit has been pushed much further along the tail. You can now make money selling something such a tiny audience that most people in the world have never heard of it.

This became a business buzzword because Anderson argued that there’s a lot of profit to be made in that tail.

Even though the popularity of each product is low, there are so many different products that their cumulative impact is huge. In the above chart, the line between head and tail seems like it’s far to the left, but the red and orange areas are actually equal.

If you can crack the distribution and marketing problems of selling into the long tail (which Anderson said was now possible with digital tools and e-commerce), you have an opportunity waiting for you. Jeff Bezos would agree.

The Long Tail in Political Analysis

In political risk, the problem with the long tail is not distribution costs. It’s production costs.

We analysts have no problem storing a report on a gold mine in Armenia on our computers and emailing them to clients. They take up no more gigabytes than a report on the US Presidential Election.

But how am I supposed to know anything about that gold mine in Armenia?

I’ve been covering US politics for years. I could write a note on the future of the Republican Party, the Biden agenda, or the structural bias of the Senate in a couple of hours with no preparation.

To research that gold mine in Armenia would require finding the experts that know about the gold mining industry, mining in the Caucasus, Armenian politics, and anything else that seems pertinent. Contact them. Set up interviews. Draft a report. Check it for mistakes with other experts. Then email to client.

It is possible to do this work, but it costs more time and money. We are producing knowledge that is harder to make and can only be sold to one client.

Getting value out of the tail

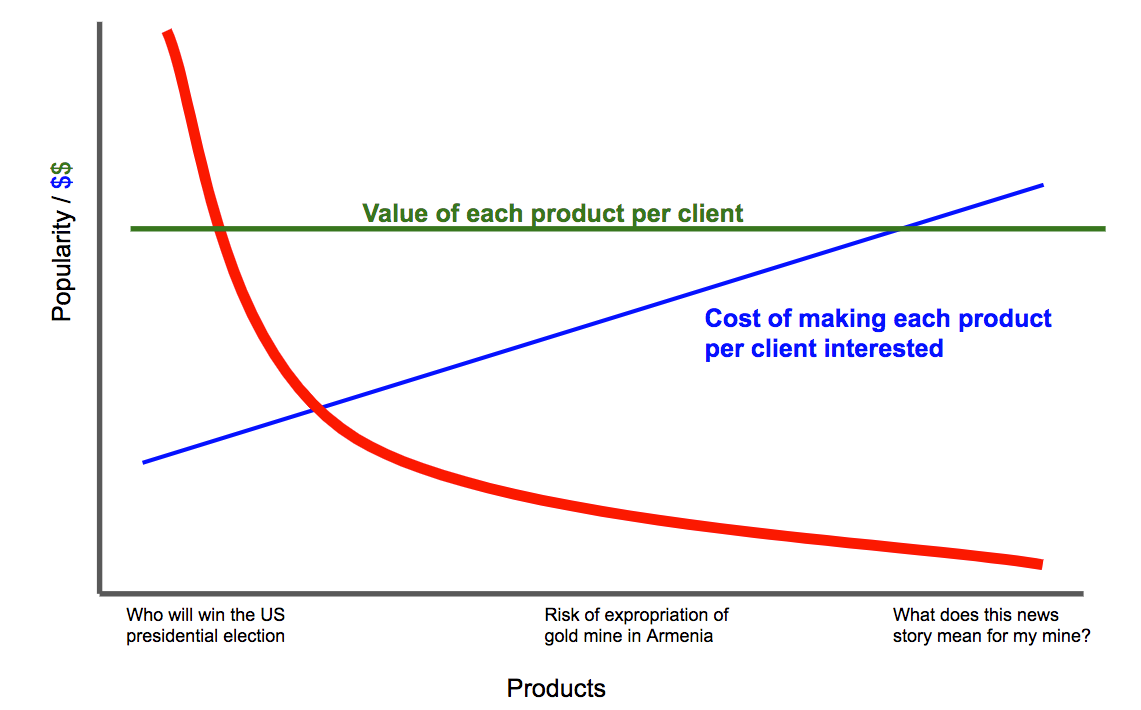

The problem here is clear. We reach a point where the cost of the product is greater than how much the client values it. This is ubiquitous when we go even further out the tail and hit the realm of daily questions.

“What is the risk of expropriation of my gold mine in Armenia” is a niche question, but it’s probably important enough to commission a report on it. When you’re going to invest millions or billions in a project, the cost-benefit of a report in the thousands of dollars is clear.

However, after the report has been delivered, the questions become even more narrow: “What does today’s bit of news mean for the risk of expropriation of my gold mine in Armenia?”; “What does this meeting one of my coworkers just had mean for the risk of expropriation of my gold mine in Armenia?”; “Should I be worried about this thing I heard at a conference on the mining industry?”

Those are good questions, but the cost of paying for a consultant every single day to answer every single one of them is certainly going to be more than the value derived.

In those cases, consultants are not hired, the question is answered in-house, and you hope that you have the requisite expertise to get it right. At the far end of the tail, there are a lot of questions to be answered, and no good way to do it.

Platforms, monitors, and the tail

This is the logic behind Two Lanterns’ training workshops. If clients are going to answer political risk questions so frequently themselves, then they ought to be taught how to do it better.

The Two Lanterns Platform was built, in part, to solve this problem in three additional ways.

First, standard templates and a faster commissioning process means that we can reduce the cost on many projects. This shifts the cost curve so that more projects are on the correct side of a cost-benefit analysis.

Second, by having the political risk community on one platform, we can have some economies of scale. You may think you’re the only one interested in a report on the likely agenda of the State Senate President in Montana in the next legislative session, but there might be a couple of other organizations that are also keen to know and are willing to split costs on a report with you. (Note: this feature is not yet live on the platform.)

Third, and perhaps most importantly of all, the Two Lanterns Platform allows the client to better manage questions on their own and to incorporate outside advice in a targeted way.

The Monitor feature permits an organization to continuously answer microquestions of what a particular news story means for them. Posting an update to the monitor entails no cost and saves time that would be spent emailing around links. Inviting an expert to contribute to the monitor lets the client pay for the amount of information they need and nothing more.

This lets the entirety of the long tail be covered: some of it by consultants that are now more affordable, some by the client themselves, and some by the two groups working together.

The Long Tail is certainly not the only problem in political risk. The next two editions of the newsletter will talk about two big ones: uncertainty and revenue. But it has been a major stumbling block for the industry and one that I hope the Two Lanterns Platform can ameliorate.

Let me know if you’re interested in joining the platform or if there are other questions you have about the industry.